The 1994 hit flick The Shawshank Redemption has a special spot in my memory ... and in my career.

Back then, I was working as a business reporter, and covering Eastman Kodak Co. KODK 0.00%↑ — which was still a big deal in Hollywood, since more than 90% of movies were shot on Kodak film. The company obviously wanted to keep it that way and made sure to connect with some of its biggest fans — the cinematographers who shot those movies.

One cool thing the Rochester-based company did every year at Oscar time was to host a pre-Academy Awards dinner for the cinematographer nominees. In 1995 — the year that Shawshank (and Forrest Gump) was nominated — I was out in Hollywood on assignment for Gannett. And I got invited to the dinner with the five nominees.

I’d be lying if I didn’t tell you it was super cool. So Shawshank is kind of another fun memory of my 22-year career as a reporter.

That flick had so many great scenes (the one on the plate-factory roof, for one; Red’s discourses on regret … and hope). But today I’m thinking about the scene where protagonist Andy Dufresne asks Warden Samuel Norton for library-expansion money — and the crooked jail-keeper tells the indentured, money-laundering trustee that the state Senate will never fork over the cash.

Said Norton: “As far as they’re concerned … only three ways to spend the taxpayers hard-earned money [when it] comes to prisons: More walls, more bars, more guards.”

That scene popped into my head this morning because I’m writing to you about the changing nature of global defense … and because of what I’m calling the “The Shawshank Corollary to Defense Strategies” — as in “more tanks, more ships, more planes.”

My Dad, William Patalon Jr., was an engineer (and a damned fine one) who spent most of his 55-year career (he worked until he was 74, and then stuck around as a consultant) in the defense business. Growing up as the son of such a remarkable man — who also nurtured a love of military history — I was fascinated by the industry that fed our family. I ended up covering defense during part of my career as a journalist and stock picker.

So I understand the “more tanks, more ships, more planes” logic.

But I also understand that there are “New Rules” here in the “New Cold War.”

And I understand that the “old” and the “new” must be logically and effectively melded.

In today’s promised follow-up to Monday’s New Cold War Report on the joint Russia-China probe of the NORAD air space “buffer zone” — and why that’s a big deal — we’ll look at those “New Rules.”

And — as I also promised — we’ll look at one company that stands to benefit from these new rules in a big way.

Lessons of History

Let’s think about this “more tanks, more ships, more planes” from a historical perspective and go back to World War II.

Let’s start with tanks, and the ground offensive in World War II in Europe. The Germans had such heavy tanks as the Tiger I and medium tanks like the PzKpfw V Panther.

Thanks to its combination of firepower, armor and mobility, the Panther is still viewed as one of the finest tanks of the war. But only 6,000 were built. The Russians had the T-34, which was built all the way through to 1958, with more than 80,000 produced. It was viewed as a breakthrough — one that actually triggered German development of the Panther V. Nearly 45,000 T-34s were destroyed during WWII — but its decades of use are testaments to its effectiveness and design.

The Allies also had the U.S.-developed M4 Sherman, which was reliable, cheap, easy to produce and easy to modify. Upon its debut in 1942, the Sherman’s armor and firepower made it superior to most of the Axis light-and-medium tanks it went up against.

As the war progressed, it was leapfrogged by tanks like the Tiger and Panther. But sheer numbers — more than 49,000 were built — made it more lethal. Having that many tanks in the field also made it easy to create a highly choreographed recovery-and-repair “network” that kept the Sherman fighting.

Factor in the bigger “system” it operated in — you know, that integrated the Sherman into the bigger “game plan” that included ground troops, artillery and the integration of the Allied’s opportunistic fighter-bombers — and you can understand how that tank’s sheer numbers overcame its shortcomings.

Little wonder the Sherman spearheaded most of the major Allied offensives from 1942 forward.

We can go through a similar exercise with ships and planes.

America’s production prowess as the “Arsenal of Democracy” was a huge advantage with shipbuilding. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, it already had been at war for more than four years – and had 11 aircraft carriers in its Navy. The U.S. Navy only had seven at that moment; they were split between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and were exceptionally fortunate that none had been docked at Pearl at the time of the December 7, 1941 surprise trike.

But even Japanese Navy Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto — the architect of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor — understood the bigger reality.

“In the first six to 12 months of a war with the United States and Great Britain, I will run wild and win victory upon victory,” Adm. Yamamoto told Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe and Cabinet Minister Shigeharu Matsumoto. “But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectations of success.”

A prophetic remark, indeed: Six months after Pearl Harbor, the United States defeated Japan in the Battle of Midway — sinking four of the Imperial Navy’s carriers. By one count, America operated 111 flattops during the war, including nine “light” and 78 escort or “Jeep Carriers.”

Japan operated 25.

The Jeep Carrier was an interesting innovation. First built on merchant-ship hulls, and later designed from the keel up, they lived up to the “jeep” moniker — providing assault support, working with sub-hunter groups, transporting aircraft and even rounding out bigger flotillas.

The Jeep Carriers, as well as Liberty Ships, exemplified America’s production muscle.

It’s the same story with aircraft. Axis countries Japan and Germany both flashed their ability to innovate — Japan with the famed Mitsubishi A6M Zero, the Nakajima Ki-84 Hayate and the N1K2-J Shiden-Kai; Germany with the Focke-Wulf Ta-152, Dornier Do 335 Pfeil and the Messerschmitt Me 262 Schwalbe, the first operational combat jet of the war. But assorted snafus, the lack of production facilities and other factors kept most of these from reaching their full potential.

So, again, Allied aircraft like the North American P-51 Mustang fighter — and the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers — were churned out in quantities that moved the war effort needle in a big way.

The Me 262, in particular, is fascinating: As the first operational jet, it represented the kind of technology paradigm shift that we’ll be talking about. The fact that only 1,400 were built — versus 15,000 for the Mustang — blunted its impact.

But here in the New Cold War, the question to ask is clear: Will sheer numbers (Old Bill’s “Shawshank Corollary”) still carry the day?

The answer plays into the defense venture I’ll talk about today.

New Battlegrounds, New Weapons

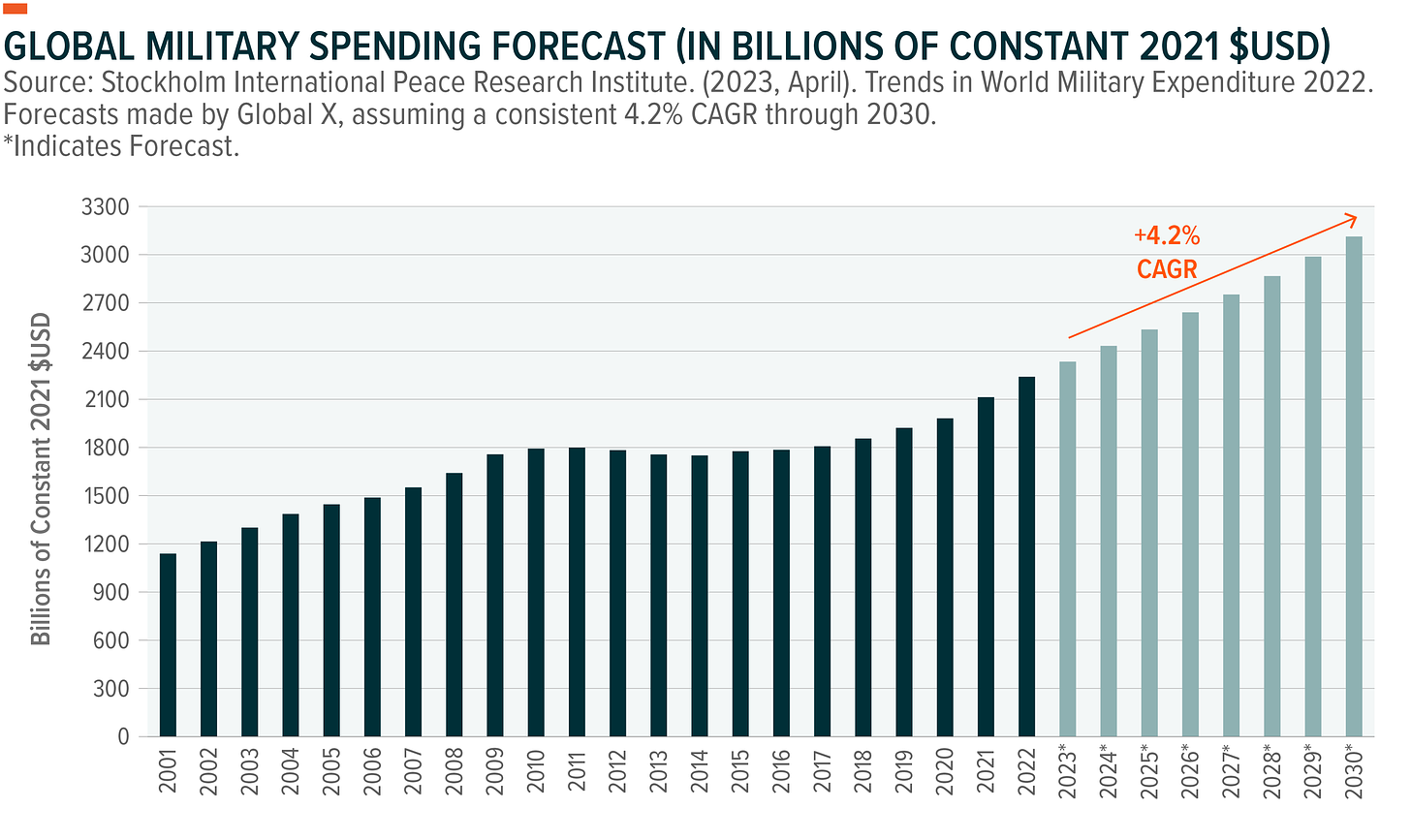

One thing we know about the New Cold War is that global military spending will continue to surge. Those outlays jumped 3.7% in 2022 to hit a record $2.24 trillion, says the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), an independent think tank that’s one of the leading experts on arms, military spending and other global security issues. And it will continue to grow — approaching $3.3 trillion by decade’s end, SIPRI says.

And the three biggest spenders — the United States, China and Russia, who are also the three New Cold War players — accounted for 56% of that $2.24 trillion total. For instance, China’s spending for 2022 was 63% more than in 2013, SIPRI says. Beijing has boosted China’s military budget for 28 years in a row.

Here’s where it starts to get interesting.

Because here in the New Cold War, we’re adding two new “theaters of operation” (battlefields) that certainly didn’t exist in World War II … and that also didn’t exist for most of the first Cold War.

The first is cyberspace.

And the second is outer space.

There’s also a third “new” realm that’s emerged as a factor — one that observant folks like you are no doubt seeing in the headlines almost every day.

I’m talking about drones — autonomous, unmanned aircraft, submarines, surface ships, combat vehicles and more. The Ukrainian military has inflicted major damage on the Russian Navy with munitions-loaded, seagoing drones. Aerial drones launched by both sides are hitting targets of opportunity in that war.

An early-year report by the Atlantic Council concluded that Iran has grabbed a spot among the world’s top arms exporters – a fact that’s helped by its global drone sales for use in the Sudanese Civil War, and on the Russia/Ukraine War battlefields.

Still sticking with my “intentionally oversimplifying” mindset, I can say that these three “new’ manifestations of the New Cold War – cyberspace, outer space and drones – have a couple of key things in common, including:

They’re New: I know, you’re saying: “You just said that, Bill.” And I did. But I need to elaborate. New battlefields require new weapons. Cyberweapons are new. So are space weapons – like the nuclear-armed “satellite killers” that Russia has allegedly deployed or targeted strikes on power grids, water systems and other critical infrastructure (and I wrote about both here). Drones as a massed weapon are new, too. So just as they did in the past with airplanes, submarines, missiles, aircraft carriers, machine guns, radar and more, military leaders will need to “learn” new offensive and defensive strategies for these new battlegrounds and new weapons systems.

They Generate Massive Amounts of Data: Just think about it. New “weapons” like a cyberweapon, or the programs that guide a “killer satellite” to its target, are digital … meaning they’re built from lines and lines of code. That all has to be stored, managed, analyzed and used.

They Create Decision-Making Challenges: More data, in real-time situations, will create mind-numbing decision-making challenges. Take drones. We’ve seen in recent years how they’re used to pick off “targets of opportunity” – but pretty much one or two at a time. But it’ll be an entirely different reality when you’ve got squadrons of drones working with human aviators in situations where the enemy is shooting back. Under the new “loyal wingman” strategy,” human fighter pilots will fly into combat accompanied by unmanned combat jets under his (or her) control. Those drones can scout ahead, provide cover for their human “wingman,” conduct side missions and more. In real time. The amount of data gathered, processed and turned into the “raw material” for those “next” decisions is staggering, too. That’s only possible with the next big creation. I’m talking, of course, about …

They’ll Need Artificial Intelligence: That’s right … AI — the crossover between “more” and “new.” The equalizing factor.

And there’s one company that I think has a chance to straddle both realms — that can fulfill my “Shawshank Corollary.”

I’m talking about the controversial tech venture Palantir Technologies Inc. PLTR 0.00%↑.

Palantir - And the First “AI War”

Zero in on that headline …

Palantir made the cover of Time as a change agent in what the news weekly headlined as “The First AI War.”

That’s right, the stealthy and misunderstood tech firm is smack dab in the middle of the Russia/Ukraine War, author and journalist Bruno Macaes explained earlier this year — in a cover story headlined: “How Palantir is Shaping the Future of Warfare.”

And Macaes pretty much described what I’ve written about before — and detailed what I said here just a moment ago: Instead of forcing gutsy forward-air controllers (FACs) to risk their lives by finding targets of opportunity, you know have tech specialists sitting in offices on one side of the world who are taking data from field sensors, reconnaissance drones and satellites, parsing it through AI algorithms, and hitting enemy targets on the other side.

“Increasingly, the real battle will take place not on the ground and not in space but inside computer code,” wrote Macaes, author of Geopolitics for the End Time. “The target coordination cycle: find, track, target, and prosecute. As we enter the algorithmic age, time is compressed. From the moment the algorithms set to work detecting their targets until these targets are prosecuted — a term of art in the field — no more than two or three minutes elapse.”

Even with the Time cover, the Palantir story is one lots of investors don’t’ know about — or understand — at least not yet.

Palantir gets a bit more than half its revenue from government contracts — and is working to build its commercial business. It has a hefty “legacy” government business — including contracts with the “three-letter” agencies such as the CIA.

It also works with each branch of the U.S. military — including the U.S. Air Force and the Space Force. Palantir’s “spiel” echoes what I’ve described here, explaining that its technology works as an “operational nervous system” that allows an armed force to “detect … deter … defeat.”

Back in May, the U.S. Army awarded Palantir a five-year, $480 million contract to start prototyping an AI-enabled battlefield analysis tool called the “Maven Smart System.”

Once developed, the Army says Maven could become part of its “All-Domain Command and Control” decision-making system.

Translated from “defense-speak,” we’re talking about a picture of the battlefield that shows where everybody is and what they’re doing – in almost real-time. That’ll let the Army move its troops where needed, coordinate air cover (like the Army did with its Sherman tanks), move supplies where needed, plan strikes and get an early warning if the enemy is mounting an attack of its own.

And a few months before the MAVEN deal, Palantir landed a $178 million Army pact for Project TITAN (Tactical Intelligence Targeting Access Node), essentially a combat-truck-mounted “ground station” to develop targeting data to “reduce sensor-to-shooter timelines,” news reports state.

Important to note here is that the contract followed a run-off against RTX Corp. RTX 0.00%↑ (formerly Raytheon), a three-year span where both competed to create a TITAN prototype.

So Palantir beat out an “OG defense contractor” to reel in that deal.

Palantir right now has a market value of nearly $60 billion. And the stock has enjoyed quite a run — up 53% year to date.

First-quarter revenue rose 21% to hit $634 million – fueled by the adoption of its commercially focused Artificial Intelligence Platform (AIP) and the signing of 41 new customers. Operating income was a record $81 million.

Trailing-12-month results include profits of $298.6 million on revenue of $2.33 billion.

The company reports second-quarter results on Monday (August 5).

Look, folks, this is a super-high-risk stock — and it’s going to be volatile. But Palantir is right now also one of the smaller, AI-focused ventures that actually has a real, measurable business. And the big pacts with the U.S. military give (some) assurance that this “AI company” will be around a few years from now.

But if you’re looking to add it to your holdings, definitely consider an “Accumulate” strategy. Start with a foundational position — and then add to it on reasonable pullbacks or as you get more cash.

There’s another new-tech defense play that I like — a lot — so much, in fact, that I have it in our Model Portfolio.

And because several of you have asked, I’ll be back next week with another defense stock or two — including one with a more conventional (but no less intriguing) storyline.

And if you like our work, consider a SPC Premium membership.

See you next time;

PLTR added to S&P 500, thank you again for covering them!

PLTR smoked earnings tonight CEO and Executive Comments:

"Strong performance in Q2 with significant growth in US commercial and government revenues. We continue to see robust demand and increased customer engagement across our business segments."